Vestibular neuritis

Vestibular neuritis is one of the top three causes of vertigo related to the inner ear (along with BPPV and Meniere’s Disease).

You may also see this condition referred to as vestibular neuronitis, acute or sudden peripheral vestibular loss, unilateral vestibular loss (UVL), or unilateral vestibular hypofunction (UVH). You may also hear about related conditions such as labyrinthitis or Ramsay-Hunt syndrome.

Read on to learn more about the symptoms of vestibular neuritis, how this condition is treated, and what to expect in your recovery.

What is vestibular neuritis?

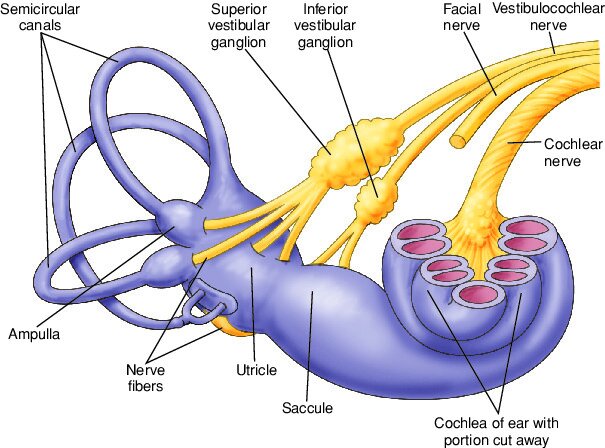

Vestibular neuritis is an inner ear infection, and is different from a middle ear infection (which affects the area around the eardrum and is typically caused by bacteria). The word ‘neuritis’ means inflammation of the nerve. In the case of vestibular neuritis, it is inflammation of the vestibular branch of the 8th cranial nerve. This condition is presumed to be caused by a virus, but what type of virus is involved in the infection is not fully known. Vestibular neuritis is sometimes associated with or preceded by a viral illness (like an upper respiratory infection). The scientific evidence is not clear, but vestibular neuritis may be caused by a virus in the herpes family and/or the type of virus that causes shingles (varicella zoster). There seem to be some cases associated with the COVID-19 virus however the research is still in its early stages.

What are the symptoms of vestibular neuritis?

Acute phase (hours to days):

Initially, vestibular neuritis causes ‘acute vestibular syndrome’ - this means sudden onset of constant vertigo, with nausea/vomiting, severe unsteadiness, and difficulty tolerating head motion.

Some people describe feeling unwell beforehand, but typically the first symptom is sudden vertigo - seeing or feeling yourself or your environment moving. This is often a sensation of spinning or rotation, which is continuous and can last hours (and sometimes days). The vertigo is often accompanied by significant nausea, vomiting, and problems with balance. The acute symptoms usually come on over a period of hours and usually peak within 24 to 48 hours, but can last several days.

Serious and life threatening neurological conditions (e.g. cerebellar or brainstem stroke) can also cause similar acute symptoms, so getting urgent medical assessment is extremely important. Other inner ear conditions can cause vertigo - so the duration and pattern of vertigo can be an important distinction when determining a diagnosis. For example, the condition BPPV can cause all the same symptoms as vestibular neuritis, however the vertigo comes and goes and only lasts less than a minute each time.

Subacute/chronic phase (weeks to months):

Once the acute symptoms improve, the vertigo resolves but you usually experience imbalance or dizziness with movement, particularly with moving your head.

What is the difference between vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, and Ramsay Hunt?

Vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, and Ramsay Hunt Syndrome are conditions that all cause similar symptoms of sudden vertigo lasting hours (to days), followed by dizziness and imbalance particularly with head and body movement.

Vestibular neuritis affects the vestibular portion of the 8th cranial nerve.

Labyrinthitis affects the vestibular portion of the 8th cranial nerve, causing all the symptoms of vestibular neuritis, however it also affects the cochlear portion of the 8th cranial nerve. Inflammation of the cochlear nerve will cause hearing loss and/or tinnitus (noise in the ear like ringing, buzzing, or humming). Labyrinthitis may sometimes be referred to as sudden cochleovestibular loss.

Ramsay-Hunt Syndrome is a related condition. It is usually caused by the shingles virus (varicella zoster virus) and affects both the vestibulocochlear nerve (8th cranial nerve) and the facial nerve (7th cranial nerve). Ramsay-Hunt causes similar symptoms of vertigo and hearing loss, but because the 7th nerve is involved, there is often a rash in the ear and/or mouth, ear pain, and facial paralysis. When the facial nerve is not working properly this causes facial paralysis (weakness in the muscles on one side of the face, difficulty moving your face and closing your eye).

How do you know if I have vestibular neuritis?

The diagnosis of vestibular neuritis is made based on your report of symptoms and a physical examination. It is important to rule out other diagnoses that can cause vertigo - in the acute phase urgent medical evaluation is necessary to make sure you are not experiencing a serious and life threatening neurological issue like stroke. Your history and a thorough clinical examination can help differentiate vestibular neuritis from other causes of vertigo, for example Meniere’s Disease, vestibular migraine, Ramsay-Hunt, labyrinthitis, or BPPV.

The physical examination includes observing your eye movements. This is because the sudden vestibular loss caused by vestibular neuritis leads to a particular pattern of involuntary rhythmic eye movements, called nystagmus. These eye movements may be visible in normal room light in the acute phase, but in the subacute and chronic phases may only be visible when using infrared video goggles.

Vestibular neuritis causes problems with the vestibulo-ocular reflex or VOR. Clinical tests of VOR function are an important part of the physical exam. These tests usually involve asking you to look at a target during head movement. Our vestibular system has a key role in keeping our vision stable and clear, so testing your VOR can tell us if you have lost inner ear balance function.

If you continue to experience symptoms in the subacute or chronic stages, you may also be sent for vestibular function tests, a hearing test, MRI, or other diagnostic testing.

Treatment for vestibular neuritis

Initially in the acute phase, medical evaluation is important to rule out serious neurological conditions. When the acute vertigo is determined to be caused by vestibular neuritis, medical treatment in the first few days is focused on helping decrease symptoms. You may be prescribed a short course of medications like antiemetics to help nausea (e.g. ondansetron, dimenhydrinate/Gravol), antihistamines to help vertigo/dizziness (e.g. diphenhydramine/Benadryl, meclizine), or benzodiazepines to help vertigo/dizziness and decrease anxiety (e.g. diazepam, lorazepam). You usually stop these medications after the first few days, as they may interfere with your brain’s ability to compensate for the loss of vestibular function. Your doctor may also prescribe corticosteroids (e.g. prednisone) and/or antiviral medications to decrease inflammation and help your body fight infection.

Treatment in the subacute/chronic phase is vestibular rehab.

Vestibular rehab for vestibular neuritis

Recovery from vestibular neuritis occurs through neuroplasticity - your brain forming new connections and pathways. Vestibular neuritis causes a loss or decrease in signals transmitted from the inner ear - this is referred to as peripheral vestibular hypofunction (‘peripheral’ refers to the inner ear organs and nerve). Vestibular rehabilitation promotes recovery through helping your brain adapt to the changes in nerve signals - this process is called central compensation (central refers to your central nervous system)

High quality randomized controlled trials strongly recommend vestibular rehabilitation for people with vestibular neuritis. These studies have also shown that it is a safe and effective treatment that helps to improve symptoms, quality of life and overall function. Starting treatment sooner, with an individualized exercise program, leads to better outcomes. There are clinical practice guidelines based on scientific evidence that provide recommendations for the optimal prescription of different types of exercises.

Physiotherapy for vestibular neuritis starts with a comprehensive assessment, to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate your symptoms and abilities. Treatment is customized to address your particular problems and goals. You will usually be given a set of exercises to perform regularly at home. These usually include exercises focused on balance and gaze stability. You will likely also be given a walking program and strategies to gradually resume your usual physical activities. Typically, physiotherapy treatment sessions occur once every 1 to 2 weeks initially and then may decrease in frequency as you get better.

Will I get better?

The typical time frame for recovery from vestibular neuritis is about two months, but there is quite a lot of individual variability. The timeline for recovery depends on the extent of the injury to the nerve and the amount of recovery of the nerve, however most people do have full resolution of symptoms. Research has shown that the amount of inner ear and nerve recovery (as measured by tests of vestibular function like calorics, VEMPs, or head impulse) does not influence your overall functional and clinical outcome. Even if the nerve does not recover, you will experience improvement in symptoms through central compensation. Recovery occurs through neuroplasticity, and vestibular rehab helps to facilitate this process.

Acute vertigo usually improves within hours to days, and then the other symptoms continue to gradually improve. You may experience residual imbalance or dizziness for weeks to months, and these symptoms can be effectively treated with vestibular rehab.

Most people only experience vestibular neuritis once. If you have another episode of vertigo after the initial acute attack, the vertigo episodes could be due to a different vestibular disorder. Other conditions can cause recurrent episodes of vertigo such as Meniere’s Disease, vestibular migraine, or recurrent vestibulopathy. Bilateral sequential vestibular neuritis is very rare - this happens when one ear was affected by vestibular neuritis, then some time later on the other ear is also affected.

Another possible cause of further attacks of vertigo after vestibular neuritis is BPPV. Approximately 10 to 15% of people with vestibular neuritis develop BPPV in the affected ear within a few weeks. Vertigo from BPPV typically happens in shorter episodes - lasting less than one minute triggered by position changes like lying down, turning in bed, getting up, bending down, or looking up. BPPV occurs after vestibular neuritis particularly if the superior branch of vestibular nerve was affected - this is because this part of the nerve supplies the utricle. The utricle is where otoconia (calcium carbonate crystals) are located, and if these are dislodged and move into the semicircular canals they cause positional vertigo.

Some people unfortunately continue to have persistent symptoms. Vestibular neuritis can be a precipitating factor for Persistent Postural Perceptual Dizziness or PPPD. If the initial symptoms of vestibular neuritis go away then later you begin to develop chronic dizziness, unsteadiness, feelings of rocking or swaying (non-rotatory vertigo) and sensitivity to complex visual stimuli (such as being in grocery stores or when scrolling on screens), this could potentially be due to PPPD. PPPD can be effectively treated with vestibular rehabilitation.

There are a number of factors associated with difficulty recovering from vestibular neuritis. A history of anxiety, fear of bodily sensations, and more frequently experiencing symptoms of autonomic arousal (like heart pounding, excessive sweating, feeling short of breath, feeling like you might faint) are associated with poorer recovery. Outcomes of vestibular rehab can be negatively impacted by anxiety or depression, migraine, peripheral neuropathy, or long term use of vestibular suppressant medications (like dimenhydrinate/Gravol or benzodiazepines).

Increased visual dependence is also associated with more difficulty recovering from vestibular neuritis. Visual dependence means relying more on your vision for balance and spatial orientation (and not using vestibular and somatosensory inputs as effectively). This over-reliance on vision can result in visual motion sensitivity and difficulties in visually busy environments. It can also lead to problems with balance when your eyes are closed. Visual dependence is a very common problem after vestibular dysfunction and is something you can improve with targeted vestibular rehabilitation exercises.

Vestibular rehab can play an important role in your recovery from vestibular neuritis, particularly in the subacute and chronic phases. We know from research that getting help from an experienced therapist sooner improves outcomes. Rehabilitation has been shown to decrease psychological distress, decrease perceived disability, and improve quality of life. Research also shows that an exercise program customized and supervised by a vestibular rehab physiotherapist leads to better results, compared to generic exercises done without support.

Want to learn more or need help with recovery? Call us to book an appointment.

-

McDonnell MN, Hillier SL. Vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Cochrane ENT Group, ed. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online January 13, 2015. [link]

Hall CD, Herdman SJ, Whitney SL, et al. Vestibular Rehabilitation for Peripheral Vestibular Hypofunction: An Updated Clinical Practice Guideline From the Academy of Neurologic Physical Therapy of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. 2022;46(2):118-177. [link]

Bae, C. H., Na, H. G., & Choi, Y. S. (2022). Current diagnosis and treatment of vestibular neuritis: a narrative review. Journal of Yeungnam medical science, 39(2), 81–88. [link]

Strupp, M., Bisdorff, A., Furman, J., Hornibrook, J., Jahn, K., Maire, R., Newman-Toker, D., & Magnusson, M. (2022). Acute unilateral vestibulopathy/vestibular neuritis: Diagnostic criteria. Journal of vestibular research : equilibrium & orientation, 32(5), 389–406. [link]

Le, T. N., Westerberg, B. D., & Lea, J. (2019). Vestibular Neuritis: Recent Advances in Etiology, Diagnostic Evaluation, and Treatment. Advances in oto-rhino-laryngology, 82, 87–92. [link]

Hidayati, H. B., Imania, H. A. N., Octaviana, D. S., Kurniawan, R. B., Wungu, C. D. K., Rida Ariarini, N. N., Srisetyaningrum, C. T., & Oceandy, D. (2022). Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy and Corticosteroids for Vestibular Neuritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina, 58(9), 1221. [link]

Bronstein, A. M., & Dieterich, M. (2019). Long-term clinical outcome in vestibular neuritis. Current opinion in neurology, 32(1), 174–180. [link]

Cousins, S., Kaski, D., Cutfield, N., Arshad, Q., Ahmad, H., Gresty, M. A., Seemungal, B. M., Golding, J., & Bronstein, A. M. (2017). Predictors of clinical recovery from vestibular neuritis: a prospective study. Annals of clinical and translational neurology, 4(5), 340–346. [link]