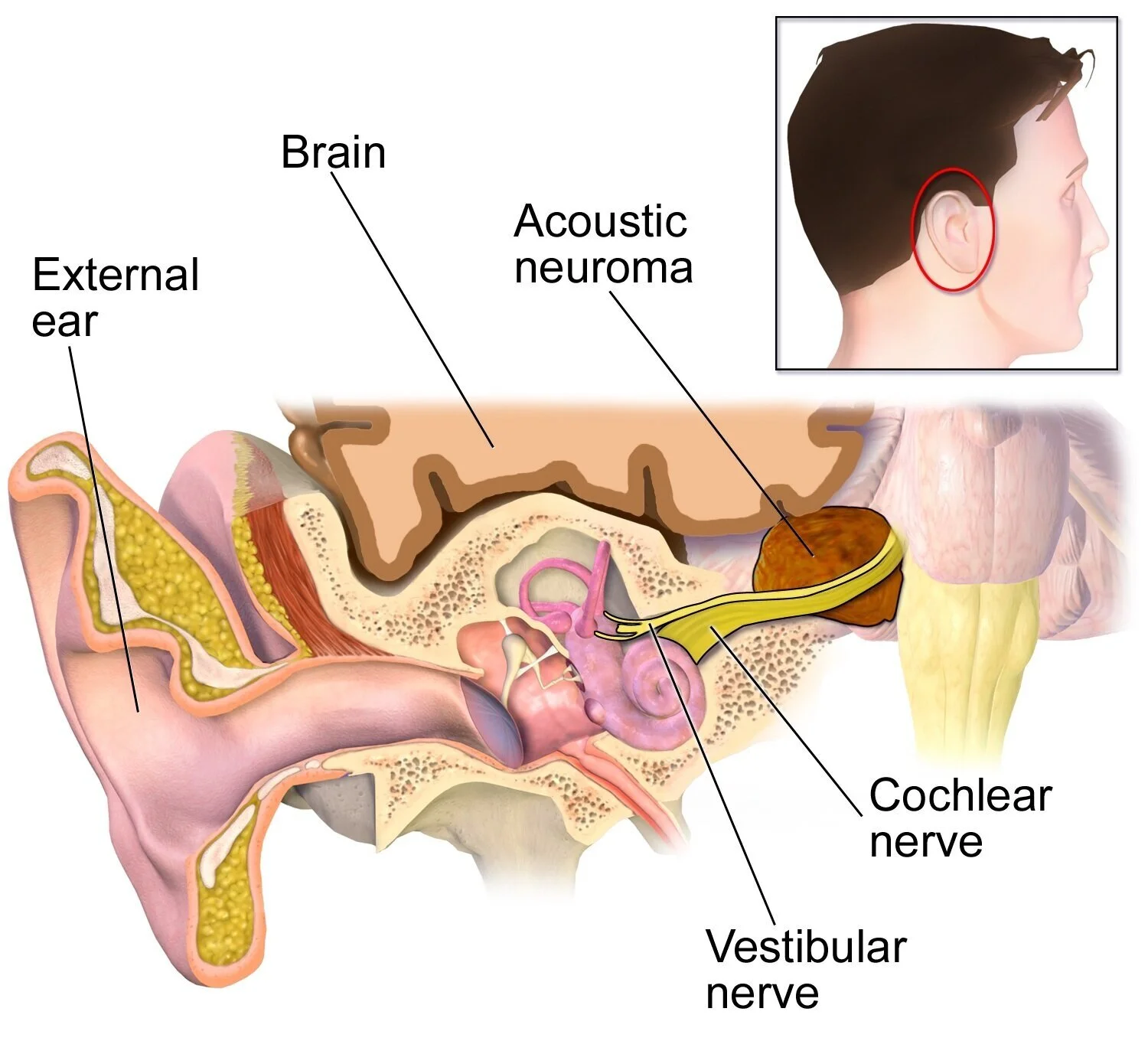

Rare vestibular conditions: Vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma)

A vestibular schwannoma, also known as an acoustic neuroma, is a benign (non-cancerous) tumour that develops on the vestibulocochlear nerve. The vestibulocochlear nerve is the 8th cranial nerve - it runs from the inner ear to the brain and is responsible for hearing and balance function. This type of tumour most commonly originates on the vestibular portion of the nerve, but both balance and hearing can be affected as the tumour grows. The vast majority of vestibular schwannomas occur on one side affecting one inner ear, but they occur on both sides in neurofibromatosis type II.

The cause of vestibular schwannoma is not known and there are no specific risk factors that have been identified. Most cases occur in people between 30 to 60 years of age. In rare cases, it may occur many years after radiation treatments for the face or neck. This type of tumour originates from an overproduction of Schwann cells, which are cells that cells normally provide support and protection to nerve cells.

Vestibular schwannomas are usually slow growing, and typically develop gradually over a period of years. They usually grow at a rate of 1 to 2 millimeters each year. Approximately 50% of these tumours do not appear to grow at all for many years after initial diagnosis.

Most vestibular schwannomas are located within the internal auditory canal, called an intracanalicular tumour. The internal auditory canal is where the vestibulocochlear nerve passes through the temporal bone of the skull. As an intracanalicular tumour grows it expands into the cerebellopontine angle. The cerebellopontine angle is the area between the cerebellum and the part of the brainstem called the pons. Vestibular schwannomas may also be extra-canalicular, or outside the internal auditory canal.

Is there a difference between vestibular schwannoma and acoustic neuroma?

Acoustic neuroma and vestibular schwannoma are two terms that both describe the same kind of benign tumour. Vestibular schwannoma is now the preferred terminology since it is more accurate, as most tumours arise from the vestibular division of the nerve and originate from Schwann cells.

How common are vestibular schwannomas?

Vestibular schwannomas are estimated to affect about 1 in 100,000 people, so are relatively rare. It is possible that increasing incidence of vestibular schwannomas is related to wider availability of MRI and increased professional awareness. Vestibular schwannomas make up about 8% of all intracranial tumours.

What are the symptoms of a vestibular schwannoma?

Hearing loss in one ear is the most common initial symptom - occurring in 90% of patients. This hearing loss is usually gradual. Tinnitus (ringing in the ears) occurs in 55% of patients and is usually present on one side. Dizziness or imbalance is an initial symptom in 61% of patients. Vertigo is less common - occurring for only 8% of patients. Headaches are also less common as an initial symptom.

If large enough, the tumor can press against nearby cranial nerves. This can cause weakness of face muscles if affecting the 7th cranial nerve (facial nerve). It can also cause tingling or numbness in the face or difficulties with swallowing/chewing if affecting the 5th cranial nerve (trigeminal nerve).

If the tumor is very large, it can press against the brainstem and cerebellum and can prevent the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid (causing hydrocephalus) - this leads to symptoms such as headaches, nausea/vomiting, and impaired coordination of movement.

How do you know if I have a vestibular schwannoma?

Taking a detailed history and performing a thorough clinical examination is important as there are other conditions that can cause similar symptoms. Ultimately, MRI is used to diagnose vestibular schwannoma. You may also be sent for hearing and vestibular function tests.

If you have a sudden or asymmetrical hearing loss your doctor will usually send you for an MRI to rule out vestibular schwannoma, although in this case the probability of identifying a vestibular schwannoma is only between 1% and 5%.

Treatment for vestibular schwannoma

You will usually be referred to an ENT surgeon and/or a neurosurgeon. The choice of treatment is determined by the size of the tumour, your age, your level of hearing and balance function, and your individual symptoms and preferences. Active treatment is usually recommended if the tumor is more than 2 centimeters in size.

‘Watch and wait’ > a conservative approach is often taken since this type of tumor grows slowly, by repeating MRI scans every 6 to 12 months.

Surgery > surgical removal of the tumor by either a translabyrinthine, middle fossa, or retrosigmoid approach. The tumor is not likely to recur after surgery, but there is a high chance of hearing loss.

Radiation > radiation treatment such as gamma-knife radiosurgery. This involves focused beams of radiation that precisely target the tumour. Radiation decreases the size of the tumor and prevents growth - the tumor will not completely disappear.

Vestibular rehab for vestibular schwannoma

In some cases, an experienced vestibular physiotherapist may be the first professional you see who suspects a vestibular schwannoma. If your vestibular physiotherapist identifies any features of this during their comprehensive interview and physical examination, it may lead to a referral back to your family physician, referral to an audiologist for a hearing examination, or recommendations for brain imaging, vestibular function tests, and referral to an ENT specialist.

After diagnosis but prior to any surgery or radiation treatment, vestibular rehabilitation physiotherapy can help decrease symptoms of dizziness, improve your balance, and maximize your physical functioning. Studies have also shown that vestibular rehabilitation before surgery limits the imbalance experienced after surgery and promotes better compensation, leading to faster recovery.

You often experience a change in vestibular function post-surgery or radiation treatment, and vestibular rehab can help facilitate the compensation process. Your brain will learn to compensate for the loss of balance function on the affected side. Your vestibular physiotherapist can provide an individualized treatment program to improve symptoms of dizziness - particularly dizziness provoked by head movement, improve your gaze stability - the ability for you to keep your vision focused while you are moving around, and improve your balance.

Physiotherapists can also provide facial neuromuscular retraining therapy if you have facial muscle weakness or synkinesis due to facial nerve involvement from this type of tumor or its treatment. Our physiotherapists have additional training in this type of treatment.

Although vestibular schwannomas are relatively uncommon, since our physiotherapists work closely with ENT surgeons and neurologists we have quite a lot of experience helping people with this diagnosis while they ‘watch and wait’, and before and after surgery/radiation treatment.

More resources & patient support:

Acoustic Neuroma Association of Canada

Acoustic Neuroma Association (USA)

Resources for clinicians:

New England Journal of Medicine review article

Canadian Audiologist article by Dr. John Rutka

Thumbnail image source: radiopedia.org